VRAI OU FAUX ? Véronique Bourgoin

06/21/2013

2013 1st June – 1st Septembre

June 25th and 26th between 2.30pm – 5pm : Veronique Bourgoin with Ursula Panhans-Buhler and some special guests : Dirk Bakker, Annegien van Doorn, Frits Gierstberg, Erik Kessels, Paul Kooiker, Jean-Louis Leibovitch, Bastiaan van der Velden, invite you in ‘Vrai ou Faux?’ living room around a conversation about Art, Photography and society

and the signature of the book “Vrai ou Faux?” published by Fotohof & Royal Book Lodge

1st June : oppening with a performance by Vero Cruz and the Hole Garden

with a musical improvisation by Reza Azard and the Forty Dollar Baby

ACT I avec les oeuvres de Julia Abstädt, Antoine d’Agata, Reza Azard, Bachelot Caron, Véronique Bourgoin, Linda Bilda, Fredi Casco, Joan Fontcuberta, Alberto Garcia Alix, Gelatin, Sara Glaxia, Gudny Gudmundsdóttir, Risk Hazekamp, Les Hole Garden, Alison Jackson, Bruce Kalberg, Adolfo Kaminsky, Erik Kessels, Martin Kippenberger, Paul Kooiker, Lutz Krüger, Jean-Louis Leibovitch, Jérôme Lefdup, Anne Lefebvre, Jochen Lempert, Boris Mikhailov, Judith Rohrmoser, Hank Schmidt in der Beek, Juli Susin, Bastiaan Van der Velden, Les Yes Men.

De la collection ROYAL BOOK LODGE les oeuvres de Abel Auer, Dick Bengtsson, matali crasset, Guy E. Debord, Andy Hope 1930, Daniel Johnston, Dorota Jurczak, Charlet Kugel, Jonathan Meese, Raymond Pettibon, Ralph Rumney, Storwal, Miroslav Tichy.

De la collection du NEDERLANDS FOTOMUSEUM les oeuvres de Violette Cornelius, Bob van Dam / Combipress, Wally Elenbaas, Bernard F. Eilers, Ed van der Elsken, Lucebert, Cas Oorthuys, Peter Martens, Hans Spies, Hannes Wallrafen, Lies Wiegman and Piet Zwart, Bernard F. Eilers avec des interieurs de Amsterdam School Binnenhuis, J.A. Snellebrand et Pieter Vorkink.

ACT II avec les archives de l’ATELIER REFLEXE et les images des résultats des workshops « Vrai ou Faux ? »

Interview of Véronique Bourgoin by Bernard Marcadé

Bernard Marcadé : The publication is presented in two volumes, would you say this corresponds to your two lines of activity ?

Véronique Bourgoin : The first volume is devoted to the private rooms in which I installed the “archives of true and false”. We assembled the archives with works I selected, done by famous and less famous artists. The second volume concerns the workshops which we had organised in Europe on the question of true and false.

B.M. : So the first volume assembles documents linked to your curating activities, in the classic sense of the term, whereas the second volume is concerned with more experimental work ?

V.B. : The Atelier Reflexe is a project I started with Juli Susin, in 1994, on the question of photography and art. The program of workshops, exhibitions and publications are designed for photographers and participants including well known artists such as Antoine d’Agata, Joan Fontcuberta, Anders Petersen, Boris Mikhaïlov, Gelatin as well as several fringe artists.

B.M. : Could we say that you now consider the workshops as a work of art ?

V.B. : Yes, in a sense, as I have devoted the second volume of this publication to them. In effect it takes on the form of a deviant newspaper (in this case Le Monde). It mixes all the archives collected in the past few years and asks us to reflect upon our contemporary world and its relationship to true and false…

B.M. : A way of editorially bouncing back to what takes place in your installation ?

V.B. : In the installation (made of real works of art in a fake room), one can effectively consult these deviated newspapers. I would like the spectator to be part of the scenery, to be inside a person’s home and to be reading today’s newspaper, at ease in a dusty sitting room… A paradoxical space in which one would have the impression that time is suspended. It is as if one was in a space ship’s sitting room spinning around the universe at the speed of light. The room is furnished in the style of the times when one dreamt of those impossible journeys across different dimensions, when you could imagine a fantastic future. I’m thinking of the years 1915 to 1930, of novels by Pawlowski, by Raymond Roussel, of Rondo-cubist furniture or by the Dutch expressionists (especially Michel Klerk’s furniture designs, “poet of shining novelty”, a utopist who held on to the cult of construction and who mastered the meeting of art and science). These rooms are presented in the installation at the Foto Museum in Rotterdam. The book, just like the installations, is shown, in the manner of a tracking shot. The passage through these intermediary spaces where the relation between true and false becomes more ambiguous and conniving are similar to time travel where one hears bribes of stories between visions squashed by the short lens of an observer distant by millions of years and those, more organic, facing infinite space…

B.M. : Is there an evident common ground between the texts and images ?

V.B. : Yes, they reflect the gnawing violence at the heart of our contemporary societies, hidden behind the iconographies and the references produced by official “fantasy”. Today’s violence is insidious, disguised, but it is so much more terrifying than ordinary violence (that of war for example), for which it is easier to be understanding. This begins with questioning the increasing erasure of frontiers between true and false. This is the dimension which appears in all the workshops that I have organised, during which I define these ideas by their associations with the collected images. This questioning points to the importance of a reading and of a point of view, in an epoch in which one thinks increasingly according to images succeeding each other, like publicity announcements, in the great cinema hall which our brain has become…

B.M. : In which context do you organise these workshops ?

V.B. : It is variable, but always in partnership. We are not an institution. These workshops are nomadic. They can take place in my space in Montreuil-sous-Bois as well as abroad. In Greece we work in partnership with the Photography Museum of Thessaloniki, in Latvia with the International Summer School of Photography, in Turkey with the IFSAK, in France with Le Bal, La Maison Populaire, Les Instants Chavirés… Each question is based on a contemporary vision. It is very important to confront oneself to the actual society in which we currently live. Like a mirror reflecting the other side of the mirror, uncovering what cannot be directly seen.

B.M. : What is the guiding line ?

V.B. : More than a school, it would rather be an open experimental project focused on photography. It started informally and developed little by little; with time we have constituted a “constellation”, around a core of interns and regular participants…

B.M. : You started with reflections on photography, and this field widened ?

V.B. : At the beginning, my photographic experiment was linked to painting. I am not at ease with “stolen” or informative photography. For me photography has always been a medium through which reality can be revealed rather than a roughly sliced cut. Even if the term “reveal”, which corresponded so well in the analogical and chemical epoch, becomes an obsolete metaphor with the advent of jet ink printers, the reveal still has a purely mystical connotation. I’ve always needed time to “watch”, to see the image appear… I also need time to establish complicity with the model…

B.M. : The model ? Which model ?

V.B. : The model, the living or still element, a person, a creature, an animal, a tree, a room, a street, which will metamorphose into a work of art… I like seeing the elements of my daily life evolve into off-the-wall situations, opening “metaphysical” spaces. In the manner of the surrealists, when I loose track of the initial meaning, the title readjusts the meaning for each of the images or series. I have formed a band, the Hole Garden, for the animated extension of my images. With this band, I try to invest in the “concept” of the occidental woman made in China… These are videos where the occidental icons are confronted by Chinese manufacturing…

B.M. : Let’s come back to your “real works of art” in your “fake room”…

V.B. : We could turn the idea around. At first it was actually a real room, mine, in which I imagined installing the art. Then the room became movable… Just like the “Boite en Valise” by Marcel Duchamp… The room thus became fake. And the works became real…

B.M. : Are these works that you install in your nomadic rooms personal choices ?

V.B. : I first concentrated on the family of artists who called upon me regularly in this sitting room, in the tradition of the end of the 19th century… Then, I refined my choices with artists implicated in the question of true and false, such as Joan Fontcuberta, for example. The themes appeared step by step: the falsification of history, forgeries, social value, mimetism, plagiarism, cloning… From this point of view the example of Martin Kippenberger is illuminating. He was obsessed with the figure of William Holden. He identified with him physically, to the point where he sent a series of postcards signed William Holden Company to Africa (where the W.H. Foundation is based)… He anticipated, in his (very artistic!) manner the actual appropriation of identity such as one can see it on Facebook…

B.M. : Do you also include “non-artistic” documents ?

V.B. : In each of these categories, one can relate works of art with documentary forms. For example retouched photographs of criminals published in the Petit Parisien in the ’20s-’40s, Chinese lighters decorated with an image of La Joconde…

B.M. : Is this method equally at stake in your deviated newspaper ?

V.B. : The newspaper implies the notion of columns. For example take the element “Fashion and Conflict” in which I associate pictures of war with documents showing the aesthetic inspiration taken from war zones and terrorism in fashion shows by Prada and Galliano where one could see a hooded convict, wearing only underwear, whip marks and a noose tied around his neck…

B.M. : Does this brings us back to the muted violence you mentioned ?

V.B. : Real war tends to look more like a Hollywood show, whereas the actual shows tone down this violence, by deviating it. The result is the banalisation of violence. The act of arranging these images and documents, in a domestic context, signifies that this violence has infiltrated every inch of our existence, in the most insidious and “normal” manner possible.

B.M. : Do I sense your strong link to the situationist philosophy ?

V.B. : The situationists used spectacular methods to combat the spectacle, just as modern power had done before them to combat revolutions. As a consequence to the world of forgery described by Guy Debord in his Society of Spectacle, they themselves used the technology of illusion as a subversive weapon. I’m thinking of the famous book written by Gianfranco Sanguinetti under the pseudonym “Censor”. This “fake” by Sanguinetti was a scandal in Italy, as it denounced, under a masked identity, the spectacle of the false terrorism practiced with total impunity by the bodies of power against the population or some of the members at the time and thus provoked disorder confusing the elite in power. More than a century back in time, the pamphlets of Paul Louis Courier underlined this same rebelliousness. I’m also thinking of Adolfo Kaminsky, another great expert in Fake, who developed infallible falsification technology, aimed not at “saving the world”, but at saving the lives of thousands of people. By forging “fake papers” for 30 years, without uproar and in total clandestinity, by being involved with the Resistance during the Second World War, with the NLF in Algeria, with the opposition during Spain’s dictatorship… I believe that numerous decisive contributions by the situationists were made prior to 1963, when it was still permitted for them to be artists. I am far from agreeing with Debord who finally excluded the artists for the sake of revolutionary principles. Even if this thinking is effectively important and decisive for the understanding of our world, I feel much closer to the ideology of Annie Le Brun. Along with the race for rationality, the increasing control of technology, the realm of pretence, the immaterial body, we are witnessing the disappearance of imagination and body as a laboratory and infinite space, and while forests are being sacrificed for the sake of planting transgenic corn, numerical references are codinginto our minds, the sensitive sphere is demarcated by the frenzied raking of the “mental forest”, as perfectly expressed by Annie Le Brun.

Ursula Panhans-Bühler

VRAI OU FAUX ? An artistic question mark behind contemporary paradises of innocence

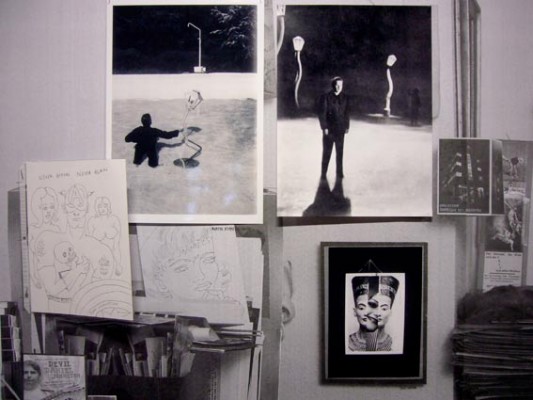

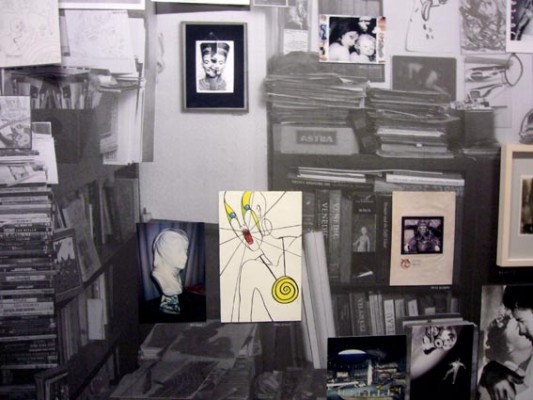

Entering one of the installations that Véronique Bourgoin has realised in various European cities over the last three years – in Hamburg, Vienna, Arles and Istanbul, with another to follow in Rotterdam in June 2013, one is surrounded by a dreamlike, contemplative situation. Black and white photo wallpapers, extending from the floor nearly to the ceiling, cover the actual rooms of the gallery space in each case, replacing them in trompe-l’oeil manner with views into interiors originating from the 19th century or the epoch of Art Nouveau, times of backward-looking nostalgia – a mood boosted by furnishings in Rococo style, heavy carpets and curtains down to the floor, and with mythological paintings and portraits on the walls. If we were to visit a real, private home from those past eras, e.g. transformed into a museum that is open to the public, we would probably get the sense – feeling either alienated or fascinated – of being transported back, in illusionist fashion, to an epoch that is no longer ours, or at least for the duration of our stay. If we were to hold photos of such rooms in our hands or view them in a book, our voyeuristic or aesthetic curiosity would, in all probability, be able to deal with the photographic image without problems; at most, we would miss the colours if the photos were black and white. The times, today and those in the past, would remain distinctly separate.

However, a completely different situation arises in Véronique Bourgoin’s installations. The photo wallpapers force themselves between us, the viewers, and the real place in which we find ourselves. The trompe-l’oeil not only breaks through the walls on which the photo wallpapers are pasted in an illusionist way; far more, it gives us the sense being there and yet not being there. Like the shock experienced when photography was invented, when the colourless “brush of nature” touched the viewer uncannily with a sense of shadowy, disappearing presence, here we find ourselves transported into a state that affects our relationship to the self. For the trompe-l’oeil articulates not only the tension of a spatially inaccessible distance but simultaneously, due to the black and white, a temporal dimension that poses the disturbing question of our relationship to our own earliest memories. This strange experience is given an additional ironic boost by the photos, images and small objects tacked to the photo wallpapers – like scattered sniper fire , originally from the art world, albeit with no orientation on the hierarchy of the art market, and from the contemporary trivial sphere. They underline their tangible status as objects with their often highly colourful appearance.

Véronique Bourgoin has formulated the problem of the disappearing dimension of depth to each of our personal stories, which is connected to the relation of true or false, in an impressive and simultaneously alarming statement : “Vrai ou Faux?” la frontière entre l’un et l’autre n’est plus un axe fixe, un axe vertical et vertigineux, que l’art a toujours su transgresser sans filet. Le Vrai et le Faux se confondent dans cette horizontalité sans fin, d’un paysage sans ombre, où la réalité ne s’oppose à rien ni à personne.” And so it is not irrelevant that the spaces installed by the artist are salons, i.e. they are interiors. As a medium, these prompt a shift towards the question of the subject’s inner axis, the world within us, while the incorporated artworks and current everyday artefacts extend this dimension associatively. “Vrai ou Faux”, therefore, is not exhausted in a banal game in which each person can make his or her choice, like the mushrooming calls of this type on Internet sites, weird language which manipulate hit quotas and a sense of belonging by means of “like-it” clicks or the lack of them. Rather, the salons of “Vrai ou Faux” – always conceived in a new way for each specific location – creates situations that touch us, gently and yet firmly questioning our cultural flight from the emotional, threateningly ambiguous vertical axis into the banality of an apparently conflict-free horizontal axis. And so they offer a chance to perceive the strange complicity between the audience and consumers on the one hand and media, advertising, politics and self-instrumentalising science on the other, a soul-selling that is voluntary on all sides: in order to evade, perhaps, the pressure of the self-forgetful, passionate fire of a self-destructive chagrin (leather).

The nomadic path of the salons – never permanently fixed anywhere – is marked by workshops at various different stages, in which the archive of the “Fabrique des Illusions”, invited artists and participants getting involved with their own personal experiences and observations all deal with the question “Vrai ou Faux” through discussions and photographic studies. In these workshops, the dissolution of the distinction between vrai ou faux has been disclosed repeatedly. The material results, supplemented by collections from Véronique Bourgoin’s archive that she has been accumulating for many years, were presented in a “cabinet of curiosities” either integrated into the salon or in a separate location. Here, the world of constant replacement, the sole passion of the economy and its accomplices, a perpetuum mobile for the satisfaction of insinuated or hallucinated wishes in the mask of desire is revealed in a satirical, dramatic fashion – one might also say: an unusual return of the anthropophagy that, in a “Trop de Réalité” as Annie Le Brun calls it in her book of the same title, causes any distinction between vrai ou faux to shatter in a closed circuit of desire. The invisible, perfidious force in the outwardly peaceful zones of our world, the complicity of visible kitsch and – initially invisible – death is supplemented impressively in these cabinets of curiosities, therefore, by schizophrenic zapping through a flickering video wall assembled from the casings of old TV sets, on which an apparently arbitrary sequence of films and videos causes the viewer to experience his own loss of control and concentration. We find ourselves in a new kind of Musée de l’Homme, in which the “antiquated nature of mankind” as investigated by Günter Anders has made astonishing cynical progess, although hardly anyone appears to take offence any more. The 19th century doll “Eve future” has not only become the ideal of an artificial human being of either sex liberated from the shame of the impure, physical body in clones, robots, avatars and replicas, turning into the end of human individuality in the idol. Following close behind came humanity’s veritable transformation into a doll, as we see from the many walking, talking examples of Barbie and Ken. “Vrai ou Faux ?” – the age of longing for felicitous metamorphoses has turned into an age of mutations, a strange mysterium conjunctionis of human drives and technology.

Véronique Bourgoin’s artistic concept does not stand alone historically; on the contrary, she has a number of historical and artistic allies. She shares with Aby Warburg an interest in Mnemosyne, the muse of memory. All the other muses that aid humanity’s productive activities are dependent on her. And although the muses have no direct opponents, the Erinyes or furies can be seen as destroyers of the muses’ work, sometimes to the point of memory loss when they take real effect. But one could also view Mnemosyne, the muse of memory, as a figure that accompanies all human activities and experiences emotionally. Nothing is lost, even though it may be suppressed. The vertical axis of which Véronique Bourgoin speaks is constantly in motion, and her proceedings revolving around “Vrai ou Faux” are challenged by artists in dizzy depth-drilling “without a net”. Aby Warburg had spoken of the “pathos formula of desire” in European history since antiquity, expressed in figures of mythology and the associated narratives. His research is expressed in the archive of his Mnemosyne Atlas: picture plates that ply the range or drifting of motifs in the balance of human emotions. There are brief keywords chosen by Warburg or explanatory essays by his co-workers referring to every thematic field. Warburg saw Nympha as a decisive figure in the re-admission of desire during the Renaissance. However, she was not a one-sided character; the maenadic could break out at any time. She was also an ambiguous figure of desire, therefore. Véronique Bourgoin’s critical diagnosis of the vertical axis of passionate memory’s shattering into a non-distinguishable, dull one-and-the-same-thing expresses the end of Mnemosyne in Warburg’s sense. But from an artistic vantage point, and in league with the invited artists and workshop participants, she questions this end, and insofar brings about a contemporary transformation of Warburg’s undertaking – in order to pull out the carpet from under the thermic, catastrophic split in the ambiguity of desire. The horror of this truth of praxis has not been eradicated; it still exists in the false part of the “trop de realité”, albeit suppressed or made invisible.

But let us make a further comment on the form of the presentation. Warburg’s photos were mounted onto panels of black photo paper. In many of her installations Véronique Bourgoin plays with the light-and-dark of the interior situation, sometimes with dark shadows caused by back-light on the walls. It constitutes a creative involvement of shadows in the embodiment of light and so in the prisoner’s conceivable escape from Plato’s cave. In the cases of both Aby Warburg and Véronique Bourgoin one could speak of clear-sighted melancholy: historically clear-sighted with respect to the history of desire that they take up and into which they wish to intervene productively with their work.

Clear-sighted melancholy become form, however, also connects Véronique Bourgoin’s work with Marcel Broodthaers and his fictive “Musée de l’art Moderne, département des Aigles”. Broodthaers also accumulated archives – of eagles, for example – actually his museum’s only departement, played through in a variety of sections. “O Mélancolie / aigre château des Aigles”, his haiku-like concetto, describes the individually obdurate melancholy that he believes many artists share with what is known less colourfully among ordinary people today as “depression”. It is clear that an artist can only frame what he knows from his own experience in such a concetto, although rather than cultivate it, he forces it into his artistic work as “porteur d’ombre”; this stems from the realisation that such a disposition hopes to escape the ambiguity of desire through Narcissistic substitute satisfaction.

Beyond this, however, there is another commonality between Véronique Bourgoin and Marcel Broodthaers: the linkage of the 19th with the 20th century, or respectively – on the horizon of the advance of a culture of “décor” for Broodthaers at most – with the 21st century. Broodthaers wanted to pull out the carpet from under any affirmation of modern, contemporary art since the 60s as the conscience of the avant-garde, which was suddenly expected to prove itself a cultural-historical time-line in opposition to 19th century bourgeois historicism. In his view, modernism had long been continuing what was the truth behind the historicism of the 19th century, a – veiling – “décor” of conditions. Therefore, he believed art was just as much entangled in a dangerous game with power – the eagle. This was to prove true, if we think back to the media instrumentalisation of art as a cultural masking of conditions and as a successor to the standard ideas, e.g. dish-washer to millionaire careers in the first half of the – particularly American – economy. Broodthaers spoke of “un monde en danger”, and all his situations – as he called his art spaces to avoid the term installation, which he found suspect – revolved around this theme. Incidentally, “raumgreifende Installation” (space-consuming installation), as the Germans say, uses a language that awakens sensitive memories. Broodthaers would certainly rediscover Véronique Bourgoin’s investigation into the abandonment of the axis of painful memories in favour of an opportunistic tolerance of everything and everyone as a prognosis in his own artistic questioning, and no doubt comment on it with his black, essentially optimistic humour.

As I see it, Jean-Luc Godard’s “Histoire(s) du Cinéma” should also be included in these affinities to the Mnemosyne. This work on the philosophy of aesthetic history also follows a principle of archiving – film sequences, fragments from poetry and literature, philosophy, musical sequences, as well as the insertion of stills: images from the history of painting and sculpture, concentrating on the modern French 19th century but also with references back to Goya and images from the Renaissance, even extending as far back as a capital relief from early Romanesque French art. The many stories do not lead to a single history, and perhaps this is where we find the – if you like – productive anarchic dimension of this sequence of videos. Godard diagnoses the end of cinema as a social form, for it has been ousted by its enemies TV and video. However, video technology allows him to generate an incredible associative mixture of artistic and documentary materials, almost amounting to an invocation not to relinquish the hopes of a reflective encounter with one’s own longing – even in face of the catastrophic turnover of wishes and events in the course of the 20th century.

At the presentation of his “Histoire(s) du Cinéma” in Cannes in 1997 Godard pulled a piece of paper from his jacket pocket, on which he had noted down a sentence taken from a newspaper. It was a quote from the recently deceased American avant-garde filmmaker, Hollis Frampton. He read this out, and the gist of it was: every artistic epoch designs an idea of a better future from memories of the past. Here, Godard was describing his own project as well. But it is also possible to refer to Véronique Bourgoin’s project in this way. Even in the fetishist fake of the 19th century, we can still recognise a trace of the ambiguous “vrai” in the conflict of desires that accompanied romantic historicism. Only with the longed for “faux”, a one-dimensional farewell to any kind of ambivalence, are we driven to the current paradise of innocence, like the storm issuing forth from there and catching as an eddy in the wings of the angel of history, so preventing him from gathering up the debris of history and reassembling it in the way Walter Benjamin had described. The wings of the spirit from Véronique Bourgoin’s series of gouache works “La dame de Clelles”, which is secretly woven into the presentation of the salon, droop with knowing melancholy. But with his clothes decorated in the diamonds of a clown and his white armoured henchman, this is also appears as a discreet, humorous reference to the twin clowns, the puckish and the melancholy, although their roles have been reversed. And so it is no wonder that “La Dame de Clelles” appears as a discreet pointer to the muse Mnemosyne, characterised by melancholy but keen attentiveness.